Koalas vs. Crows: An Evolutionary Theory of Software

Is there any more charismatic animal than the much maligned koala? Said to "defy evolution", they sleep 20 hours a day, survive solely on eucalyptus leaves - a food source not only nutritionally poor but indeed toxic - and famously don't recognise that food source detached from a tree. And yet, they have not only survived but thrived for more than 25 million years, outcompeting faster, stronger and smarter animals. How is such a thing possible? Koalas are hyper-specialised to a very specific niche: they are the only animal that eats eucalyptus leaves.

A koala sitting in a eucalyptus tree

A koala sitting in a eucalyptus tree

Pandas, who are more closely related to whales than to koalas, evolved independently to fit the same niche, but with bamboo in place of eucalyptus, in a completely different part of the world. Not only has evolution selected for the dumbest animal alive, it has done it more than once. This adaptation - expending as little energy on brain power, or indeed anything else - works.

Compare koalas and pandas to crows. Crows are famously intelligent, demonstrating tool use, social learning, long term memory and even "metacognition", i.e. thinking about thinking. They dominate not one but many niches all around the world. Crows can survive anywhere. However, their big brains take a lot of energy. Crows are "opportunistic feeders" - they will eat anything, and they expend a lot of energy finding food.

A carrion crow (corvus corone)

A carrion crow (corvus corone)

An even better example of this high-adaptability high-energy strategy is the common rat. Rats are a pest precisely because they outcompete native species in pretty much any niche they find. They explore their environment, using their advanced spatial awareness to build a "mental map" of the world around them, forming strategies tailored to its specific circumstances.

The trade-off: rats binge-eat. They consume everything they can and won't stop eating when they've had "enough". I often wonder if we hate rats precisely because they remind us of the things we hate about ourselves. Like us, all the destruction wrought by rats, consuming relentlessly, destroying ecosystems, serves one purpose: fuelling their enormous brains so they can survive and reproduce.

Tiny low-energy brains and huge high-energy brains, two wildly divergent survival strategies, both result from the same process: evolution. It seems counter-intuitive, and yet we see something strikingly similar in software development as well. I'm going to do my best now to convince you that it's not just something similar but the same thing.

The Energy Cost Theory of Software Evolution

Both rats and crows exhibit tool use. It's one of those evolutionary strategies that can work very well, and, indeed, it's a strategy that humans take to great extremes. Software is a tool, and, like rats and crows, we use it to increase our chances of survival and reproduction. As such, the forces that drive evolution "bleed" into our tools when we're building them.

The evolution of biology is driven fundamentally by evolutionary pressure. Evolutionary pressure is, most of the time, about the scarcity of energy in a system. Very roughly, "energy" is the capacity to make things move - whether that's the movement of a chemical signal in the brain or the movement of a muscle. Energy is the "currency" of life, and, as such, "competition", in the evolutionary sense, is always, directly or indirectly, competition for energy.

To this end, evolutionary adaptation often takes the form of an "energy cost" trade-off. You need energy to get energy. Organisms that can do more with less have an advantage, and there are typically two ways to do this: get more energy out of an ecosystem, or use it more efficiently.

The former is what crows do. The latter is what koalas do.

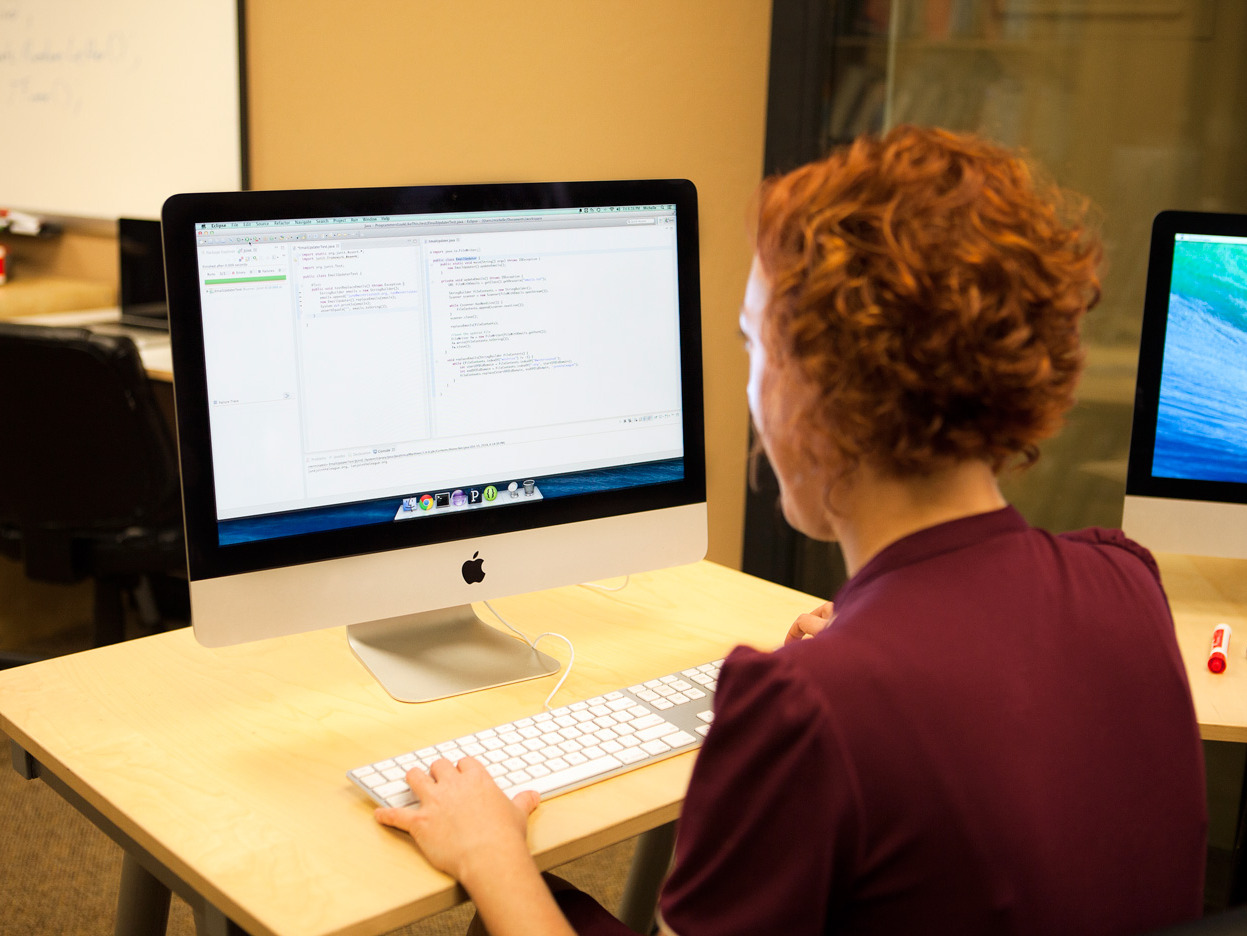

A software engineer using software to build new software

A software engineer using software to build new software

So what's the "energy" in the software ecosystem? Well, I put it to you that it is, in fact, literally energy. Specifically, I'm interested in the "energy cost" of big human brains. I think it's a major factor in the design of software. Software is unusual in that, unlike most other human tools, the "energy cost" of using it comes down almost entirely to what we tend to call "cognitive load". I wrote a bit about how tech optimises for cognitive load in my last piece.

Software has to be "as easy to use as possible". Here's the thing: that means different things in different contexts. The energy cost "trade-off" - in software as in biology - can be done in two different ways: get more, or use less. In a word, I believe there are broadly two distinct forms of software: koala software and crow software.

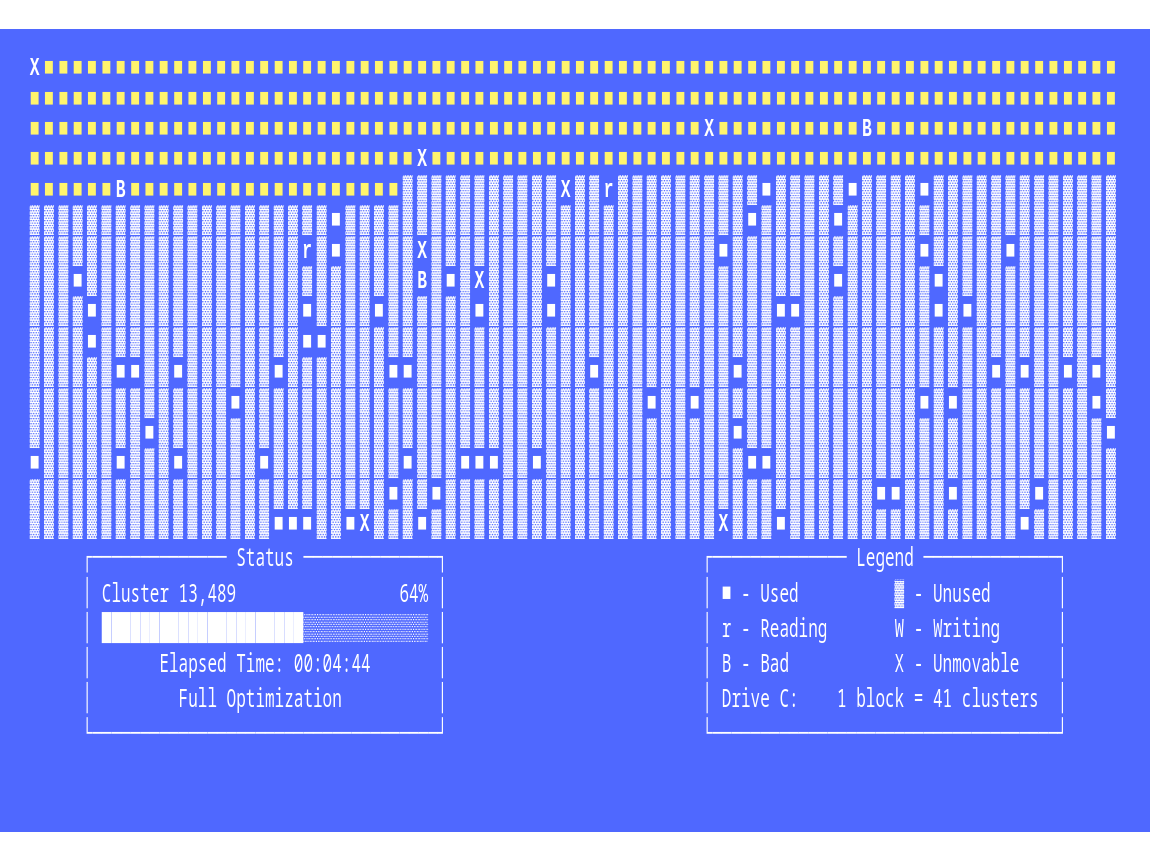

A mock-up of 90s-era defragmentation software, courtesy of ShipLift.io

A mock-up of 90s-era defragmentation software, courtesy of ShipLift.io

I'll give you some examples. Koala software is things like SMTP and FAT32, you know, the tech that's so old and shit that it should by rights have died out years ago, but hasn't because it is so easy to use. CSV and JSON are really good examples of koalas that have outlived crow competitors like XML and SOAP. In these really specific niches, dumb is everything.

Crow software meanwhile is anything that can be described as having a "learning curve" or "power users". The Adobe suite. Blender. DAWs, IDEs. Indeed, anything HN likes to rail against - Ansible, Terraform, Kubernetes. When a piece of software needs to handle a broad range of use cases - especially to an industry standard - it's better to be smart, adaptable and, above all, opportunistic. (Perhaps a better word is "enterprising".)

These two broad categories of software coexist and thrive in different niches. I want to talk a bit about what I believe those niches look like and how they form.

The Unix Philosophy

In 1978, Doug McIlroy documented a set of precepts for software development in the Bell System Technical Journal. These ideas had emerged from the collaborative culture of Bell Labs in the 1960s and 70s, where developers like Ken Thompson, Dennis Ritchie, and McIlroy himself were building Unix under tight hardware constraints. Together, they effectively codify what became known as the Unix Philosophy.

Doug McIlroy and Dennis Ritchie in 2011

Doug McIlroy and Dennis Ritchie in 2011

Rule number one of the Unix Philosophy: "Make each program do one thing well. To do a new job, build afresh rather than complicate old programs by adding new features." There is no more succinct summary of koala software.

Or so it would seem.

In 1989, prominent Lisp developer Richard P. Gabriel published an essay titled Lisp: Good News, Bad News, How to Win Big, in which, among other things, he laments the rise of what he calls the "MIT Approach" to Unix development. The essay is widely known for a single section, titled "The Rise of Worse is Better", which was included in The UNIX-HATERS Handbook published in 1994. Gabriel's argument is, in a word, that "it is often undesirable to go for the right thing first. It is better to get half of the right thing available."

Clearly, something had happened between 1978 and 1989. In the intervening decade, "do one thing well" had ceased to be a koala principle and had become a crow principle.

How is such a thing possible? We've all used the POSIX core utilities. Pretty much anything you need to do on a Unix-like system you can do with a more or less clever pipeline of awks, greps and seds - and, most of the time, you'll be using the same flags Thompson, Ritchie and McIlroy used in the 70s. They "do one thing well".

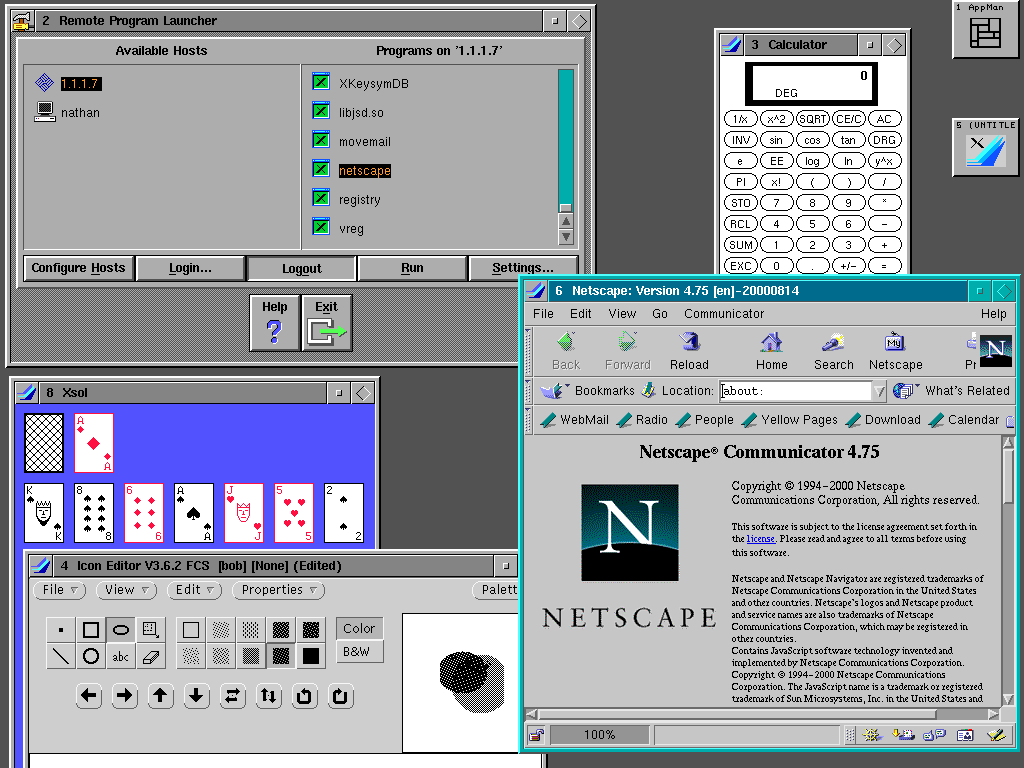

An X terminal running various X11 applications hosted on a remote server, courtesy of Nathan's Toasty Technology page

An X terminal running various X11 applications hosted on a remote server, courtesy of Nathan's Toasty Technology page

In 1984, the developers on Project Athena, at MIT, started work on a windowing system. The "one thing" to "do well" is pretty straightforward: Unix needed a standard implementation of WIMP - windows, icons, menus, pointer. The result - the X Window System - is probably the best example of the "MIT Approach" in history: a towering monolith which turns every desktop into a distributed system, a piece of software so punishingly complex that it remained hidden behind toolkits like Qt and GTK+ for most of its lifetime.

And yet, what a lifetime! It's only now, some four decades later, that Wayland promises to replace X11 for good. This is a promise we've heard before, and, so far, X has outlived every competitor. There is something to be said for a piece of software that hasn't had a new major version in nearly four decades.

Both the core utilities and X have survived, and they have done so by means of two diametrically opposed strategies. On the one hand, we have pure koala tech. Everything is a string. Output is the same for human or machine. Dumb wins. On the other hand, the majestic crow: X runs on pretty much every Unix system in the world because there is no obscure edge case it cannot handle. X eats everything.

Disruptive Innovation

In 1995, Clayton Christensen published an article in the Harvard Business Review titled Disruptive Technologies: Catching the Wave, in which he expounds his theory of "disruptive innovation". In a word, the theory goes like this: disruption is the "process", originating in "low-end" or "new" market footholds, which takes market share from incumbents by employing a significantly different business model - in a word, "worse is better".

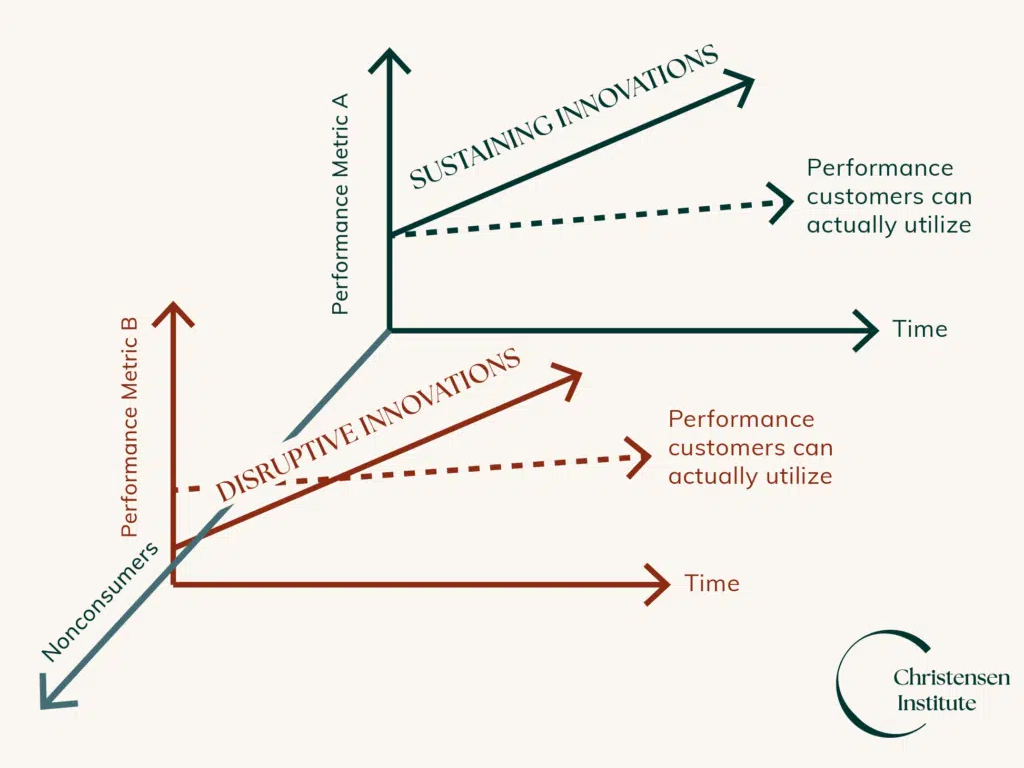

A diagram visualising the difference between disruptive and sustaining innovations, from the Christensen Institute

A diagram visualising the difference between disruptive and sustaining innovations, from the Christensen Institute

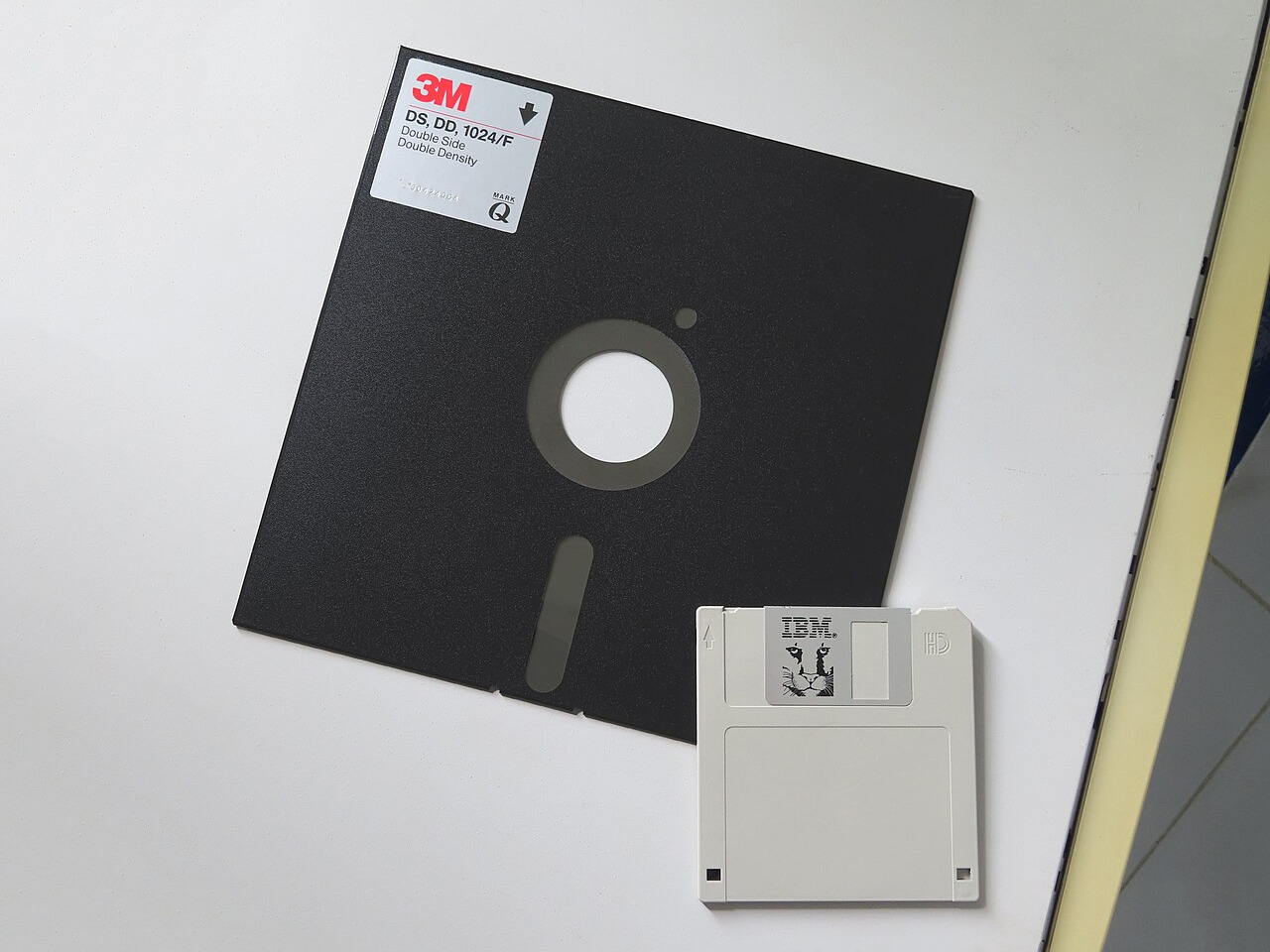

It's important to understand the context of this idea. Christensen was aiming to explain a phenomenon that was increasingly common at the time: large businesses failing despite doing "the right thing". He uses some specific examples to illustrate the idea, most notably the introduction of 5.25 inch floppy disks, materially inferior technology compared to the existing 8 inch disks that were already widespread, which nevertheless replaced them everywhere.

An 8 inch floppy disk compared to a 3.5 inch floppy disk

An 8 inch floppy disk compared to a 3.5 inch floppy disk

Importantly, it wasn't the technology that was innovative per se. On the contrary, the new 5.25 inch disks manufactured by Seagate were made of off-the-shelf parts. The thing that was disruptive was the business model: the incumbent, Control Data Corporation, was targeting big businesses and "power users". They had effectively no product for ordinary people with PCs. Seagate catered to this "low-end market" and became massively profitable.

Disruption, in other words, is when a koala beats a crow.

Sustaining Innovation

Now, let's not kid ourselves, I know who my audience is. We love disruption. We love koalas. As such, we tend to ignore the other side of the coin, the innovation which is undertaken by incumbents, the work big businesses do to hone their products for their existing customer base.

This kind of innovation is what Christensen calls "sustaining innovation". The label isn't ideal - "sustaining" sounds like "maintaining", like a "lack" of innovation. What "sustaining innovation" actually refers to is the innovation that involves adding new features - filling in Gabriel's remaining 50%. In a word: when better is better.

What does it look like when a crow beats a koala?

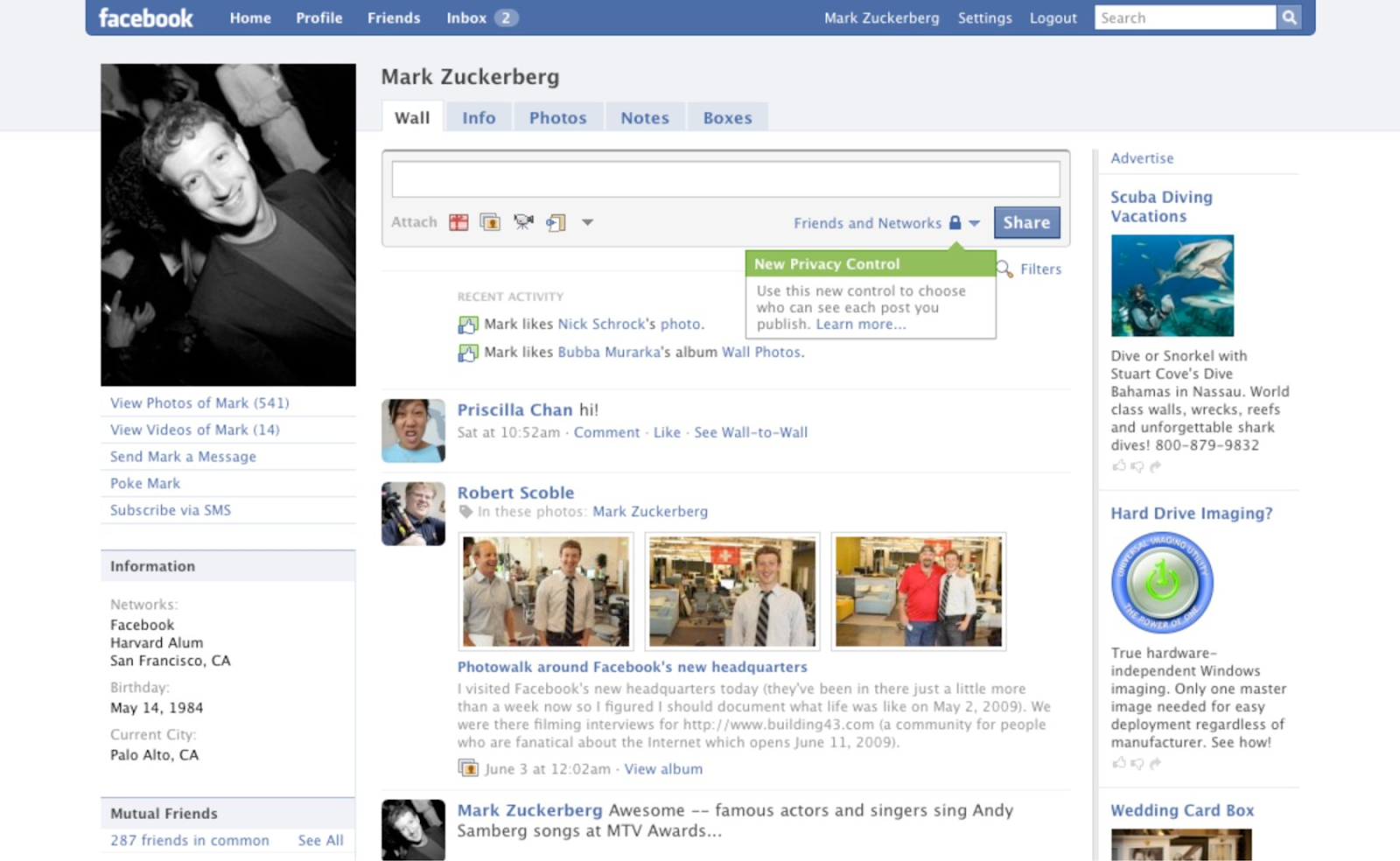

I'll never forget when jQuery first appeared on the scene. It was a fun time to be doing Web dev, lots of hype around something we were calling "Web 2.0". There was this new MySpace competitor that had just rocked up on the scene calling itself Facebook. The things it did with front-end - with JavaScript - were astounding.

Facebook in 2009

Facebook in 2009

In 2005, a guy called Jesse James Garrett, who was working at Google, published an article in Adaptive Path titled Ajax: A New Approach to Web Applications. Garrett had "discovered" an obscure part of the JS spec called XMLHttpRequest. We were all surprised, to be sure! XHR had been in the spec since the late 90s - Web devs just didn't know about it, and, more importantly, we didn't realise that it had actually enjoyed mainstream browser support for some years, after Mozilla had reverse engineered the Microsoft implementation and put it in Firefox.

Now XHR (for the benefit of the younger readers, it was what was replaced by the fetch API a decade later) was a royal pain in the arse to use. The cognitive load involved was high. It had a steep learning curve. But: Google was using it to build truly beautiful software. We could all see the potential. Between the two of them, Facebook and Google were raising the bar for all of us. So, we went away and did the work to wrap our heads around the XHR specification. The problem was that we didn't need most of what XHR could do. We had specific, simple use cases. What we needed was a koala, not a crow.

The homepage of script.aculo.us in December 2010 and also in August 2025

The homepage of script.aculo.us in December 2010 and also in August 2025

Many of us wrote our own little libraries that would handle the boilerplate. Some of them even got big and famous - Dojo and Prototype are still around to this day (indeed the Script.aculo.us homepage is still online - check it out if you want an idea of what the general vibe was like at the time).

It wasn't until 2006, however, when a guy called John Resig finally nailed it and the world got to meet jQuery. You included a single JS script in your HTML head, and voilà, you had the dollar sign at your disposal. As far as low cognitive load interfaces go, the jQuery dollar sign is an exemplar. It was like magic.

Suddenly Stack Overflow was flooded with jQuery code. jQuery websites exploded overnight. They were everywhere. I say "were" - they still are everywhere. Indeed, perhaps most importantly, jQuery began to be used by serious businesses, in particular by tiny startups who were out to take low-end customers from the big tech firms - and, of course, to create new markets among people who previously might not have consumed Web-based software.

You can guess what happened next. Slowly but surely, as developers wired more and more jQuery code together into sprawling mountains of spaghetti code, it began to dawn on us that maybe jQuery wouldn't cut it beyond a certain level of complexity. Suddenly, we needed a crow. We knew what the thing we needed looked like, but optimising for the existing ecosystem was above our pay grade.

It wasn't until 2013 that we finally learned how Facebook themselves were doing it, when they open-sourced their front-end framework, now known as React. Of course, React wasn't first on the scene. There were plenty of attempts to make jQuery better - or, indeed, to replace it with something else entirely. In the 2010s we were all playing around with libraries like Backbone, Meteor and Knockout. Those of us who were doing dev at the time will no doubt recall with fondness the first time we had a go with Angular or Vue. Vue, for me personally, was the most joy I had felt dealing with JavaScript since the early days of jQuery.

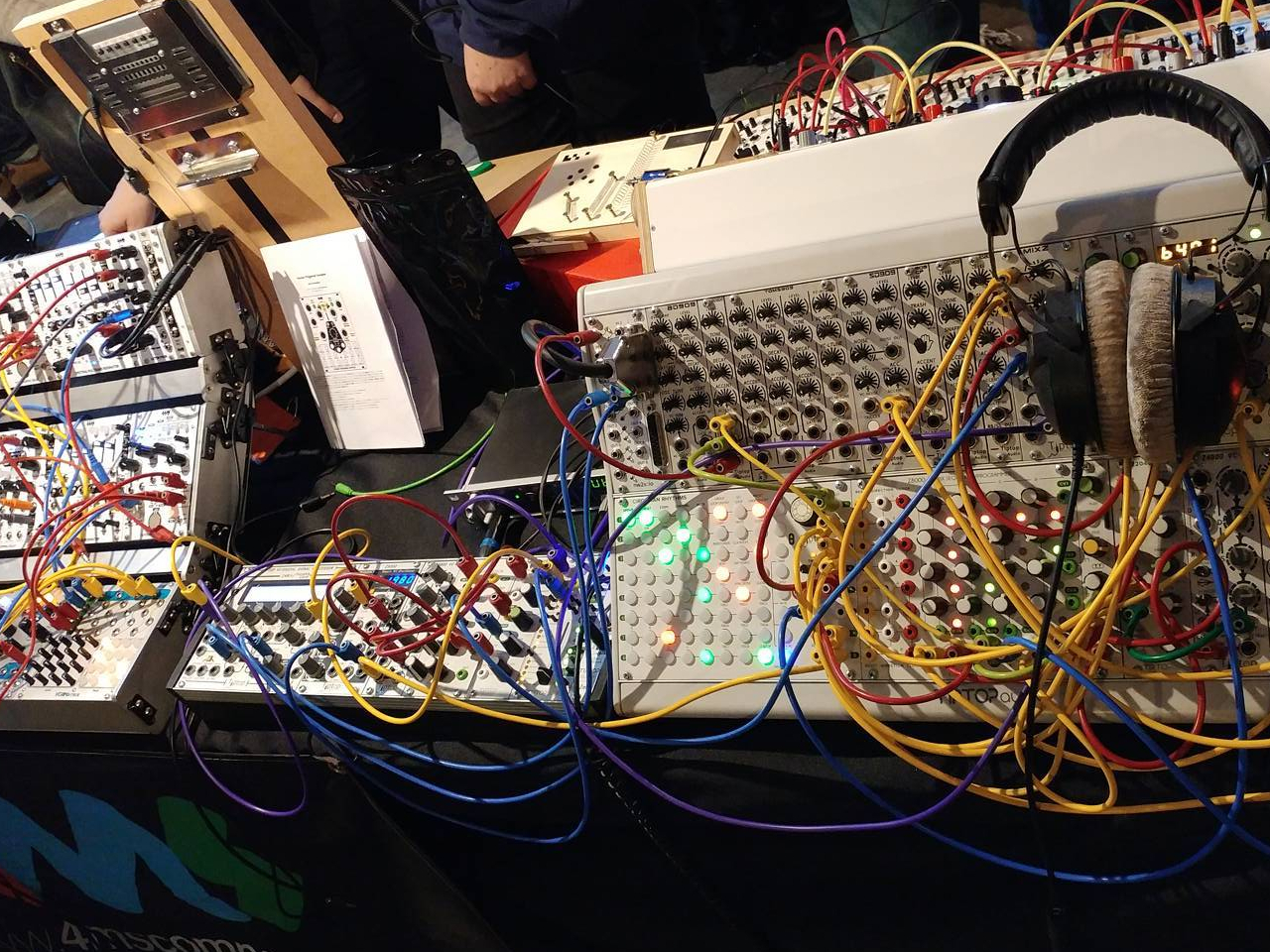

A modular synth set-up - many simple components are connected with cables - the cables are at risk of becoming tangled

A modular synth set-up - many simple components are connected with cables - the cables are at risk of becoming tangled

This, in a word, is how a crow beats a koala. Koala tech lends itself to a modular design. We're all guilty of it: you refuse to buy the big expensive software because you can hack your way most of the way there by wiring a bunch of smaller apps together into a "workflow" or a "pipeline".

Eventually, there comes a kind of inflection point. The pipeline has grown large and unwieldy enough that the cognitive load involved in maintaining it outweighs the cognitive load involved in learning a new, more integrated, piece of software. At that point, the energy cost trade-off swings the other way. The niche has changed.

Adapt or Die

Of course, I need merely to scroll through HN right now to find any number of articles calling for an end to JS frameworks, arguing that Web Components and HTMX will replace them for good and all, and so on and so forth. We love koalas. They are charismatic animals. But crows deserve love too.

Strictly speaking, crows and koalas don't actually compete - they exist in different niches. The key thing to take away here is that niches change. One strategy is not superior to the other. Instead, it depends on the complexity of the most common use case.

Koala software (SMTP, JSON, HTMX) dominates when 50% is enough. Crow software (Kubernetes, React, Photoshop) thrives when you need the other 50%. In reality, one never truly replaces the other. Instead, one replaces the other for a certain share of the market, and that market share changes in size as the ecosystem changes, just as populations of organisms do.

The next time you find yourself arguing that a piece of software is "overcomplicated" or "too simple", remember that your argument is necessarily qualified by the realities of the niche you're in as a user. I never missed React before it existed because none of my customers expected it. Once Facebook and Google showed end users what was possible, my niche changed.

If history is anything to go by, I think it's safe to assume that any niche will change eventually. I hope I've given engineers and entrepreneurs some language with which to discuss where they are in their market. Are you in a koala niche or a crow niche? What would cause it to tip from one to the other? How soon is that likely to happen? Once you understand that much, you can decide what it means for you to build "the right thing".