When Is Tech Not Hype? Tulips, Toilets, Trains - and Tabs

What do I do when I first wake up? I grab my phone. I'm reading the news, browsing Reddit, reading articles on HN, looking up the weather and anything else I might need to know about during the day. It's not until I open my tabs view, to switch back to something, that I realise I've managed to open half a dozen tabs within the space of minutes.

In 2004, Mozilla Foundation placed a two-page ad in the New York Times announcing version 1.0 of Firefox. "Are you fed up with your web browser?" the ad asks. "There is an alternative." Mozilla had a compelling story: in the wake of the browser wars of the 90s, in which Internet Explorer had ascended supreme over Netscape Navigator, Firefox, which started life as an experimental fork of the defeated browser, had "risen from the ashes" to defy Microsoft.

Firefox ad in the New York Times, 2004

Firefox ad in the New York Times, 2004

Many users were disgruntled with Explorer at the time. Firefox boasted a number of improvements, including pop-up blocking and extensions. Perhaps the most visible difference, however, was tabbed browsing. Tabs weren't new, by any stretch of the imagination. Firefox wasn't even the first web browser with tabs. And yet, for some reason, the time was right. Browser tabs symbolised something deeper: they were a user interface for the new millennium.

What is "hype"?

Curb brokers on Wall Street, 1920s

Curb brokers on Wall Street, 1920s

It's so easy to talk about how tech is so scammy nowadays, how hype is everywhere nowadays as though hype were a side effect of social media or the post-truth era more generally. We would be greatly mistaken to think about hype this way. Hype is as old as capitalism. Indeed, hype is an essential component in the mechanics of capitalism broadly - arguably it is the thing that makes capitalism capitalism as opposed to any other currency-based economic system.

Broadly, when we talk about hype, we are talking about the so-called "business cycle". Two broad schools of thought presently dominate discourse on this macroeconomic phenomenon:

- The Schumpeterian school, after the work of Joseph Schumpeter (1883-1950)

- The Minskyite school, after the work of Hymen Minsky (1919-1996)

The two models were seen as contradictory for a long time. Indeed, they have largely been ignored, during the neoliberal consensus era, as "heterodox" economics. After the global financial crisis of 2009, however, renewed interest in the two theories led to increasing dialogue between them, and a period of consolidation has followed.

The Schumpeterian theory of the business cycle is based on the concept of "creative destruction". (It's important to say explicitly, right off the bat, that Schumpeter's "destruction" is not the same as Clayton Christensen's "disruption", which we will have cause to talk about in future posts.) Creative destruction is the process by which innovation replaces an existing technology with a new one. The most obvious example to anyone living in the 21st century is that of music media, from vinyl to 8-track to cassettes to compact discs to MP3 players to streaming.

The Minskyite theory of the business cycle, on the other hand, is about finance, investment and speculation. Minsky's Financial Instability Hypothesis in a few words: during times of prosperity, when debts can be paid, investors go looking for innovative instruments. Before very long, it becomes clear that some new technology is going to revolutionise the way we live. Investors start leveraging their investments, trusting blindly in the "bigger fool" who will buy for a higher price. At some point there is no bigger fool. The entire thing comes crashing down, creating a crisis. The cycle begins anew.

If like me you remember blockchain, you will recognise both of these narratives. More specifically, you will recognise both of these as narratives fundamentally about the concept of hype.

The earliest documented example of hype is the Tulip Mania of the 1630s. If we want to talk tech hype specifically, just look at the 1920s: cars, radios, and home appliances flooded into American homes. Wall Street piled into a booming economy, speculation soared, and the decade ended with the Great Depression.

But here's the thing: cars, radios, vacuum cleaners, washing machines, toasters... none of these technologies were "just hype". These were genuinely transformative innovations, and they did in fact revolutionise the way we live. Can you imagine a world without these things now? I can't.

So what's going on here?

The Infrastructure Loop

My favourite user interface has to be the flush button on a toilet. I would recommend with all my heart to anyone: have a go at fixing a toilet once in your life. You will be astounded at the complexity of the hardware involved. You will end up admitting defeat or learning more than you ever wanted to about fluid dynamics under the influence of gravity. And yet: a single button! Truly, the iPhone of the Industrial Revolution.

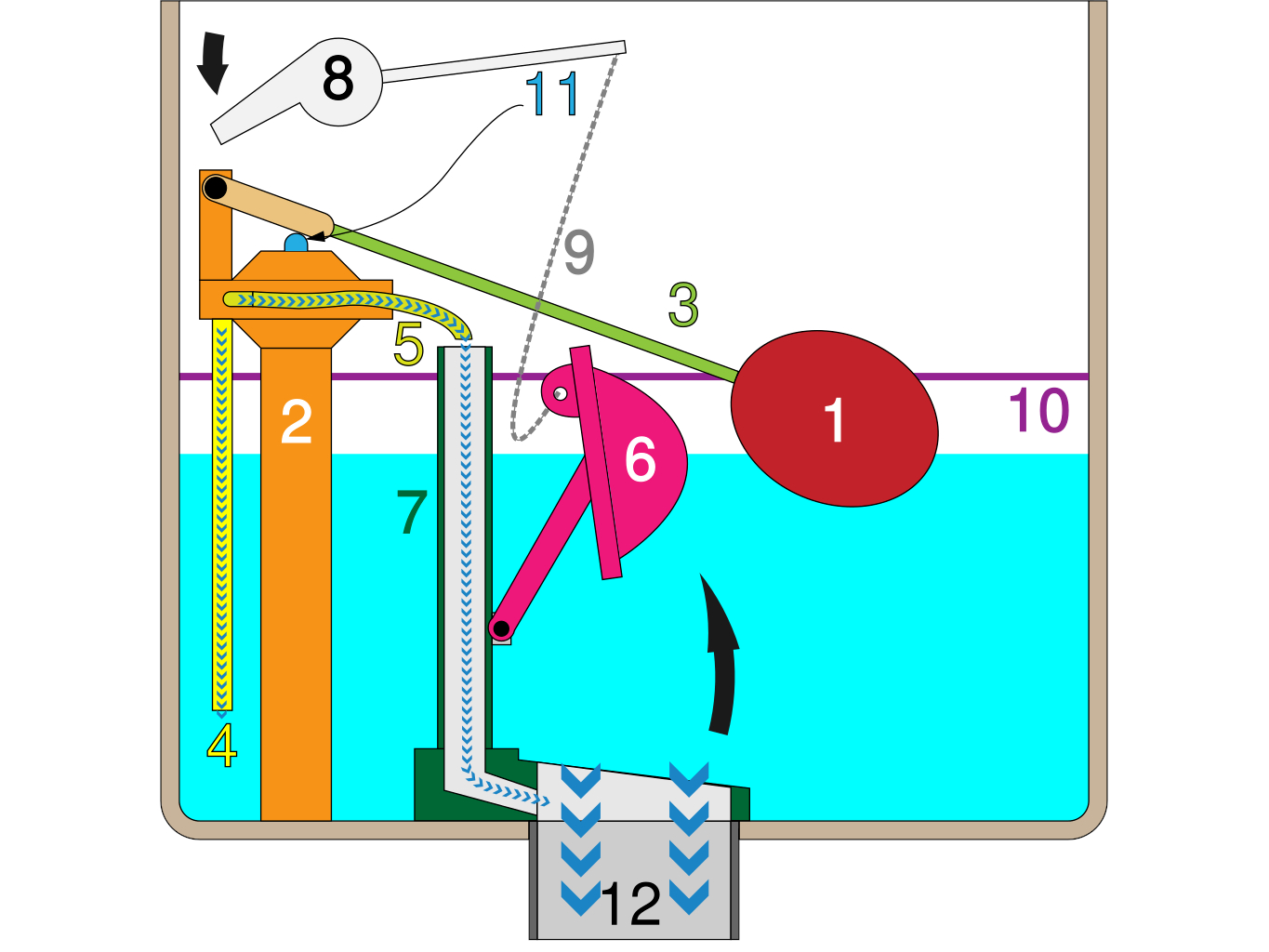

Diagram of a gravity toilet cistern showing 1. float, 2. fill valve, 3. lift arm, 4. tank fill tube, 5. bowl fill tube, 6. flush valve flapper, 7. overflow tube, 8. flush handle, 9. chain, 10. fill line, 11. fill valve shaft, 12. flush tube

Diagram of a gravity toilet cistern showing 1. float, 2. fill valve, 3. lift arm, 4. tank fill tube, 5. bowl fill tube, 6. flush valve flapper, 7. overflow tube, 8. flush handle, 9. chain, 10. fill line, 11. fill valve shaft, 12. flush tube

And that's just the bit that's in your home. None of this works at all without an industrial scale system of plumbing, with all the complexity involved. The flushing toilet was just hype until the infrastructure was built around it to make it viable.

I argue that there are two elements that need to be present for a technology to pass from the "just hype" to the "genuinely revolutionary" phase:

- A foolproof user interface: using it requires minimal cognitive load

- Ubiquitous infrastructure: it is available everywhere

These two elements feed each other in a loop. There is no reason to build infrastructure until there is a critical mass of consumers who will pay for it. There is no reason to build a beautiful user interface until there is an existing infrastructure that makes it viable. It's the chicken and the egg, and this loop doesn't run at all without some kind of driving force: someone needs to sell the dream.

This, I argue, is what hype is. To put it another way: tech is always hype.

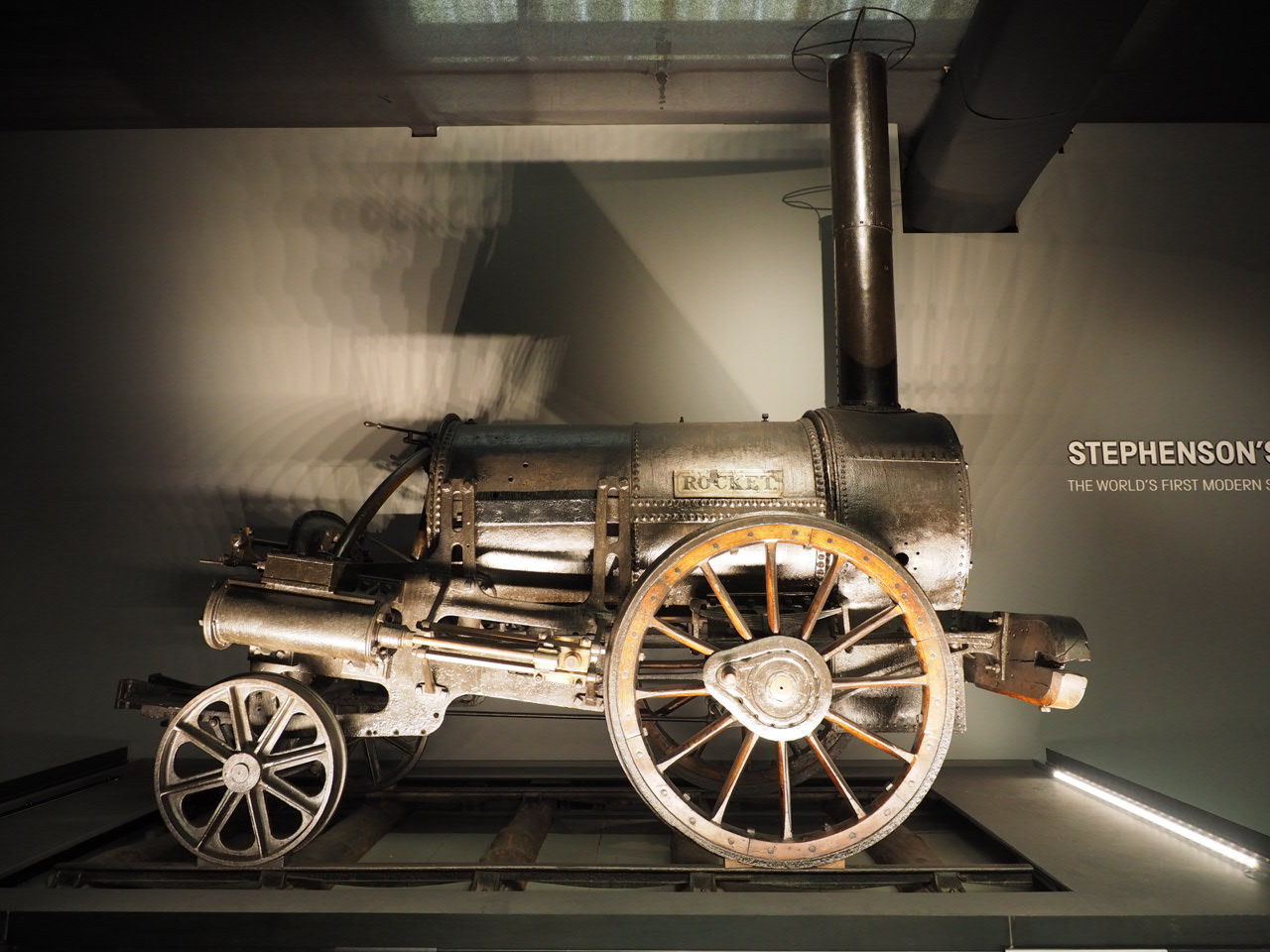

Stephenson's Rocket, the first steam locomotive, 1829, in the National Railway Museum

Stephenson's Rocket, the first steam locomotive, 1829, in the National Railway Museum

Can you imagine looking at a steam train for the first time, back in the Victorian era? And it only runs on rails? There is obviously no future for such an invention. A fun toy, nothing more. Anyone investing in this technology is buying the hype. Then, one day, there are railway lines spanning a continent.

Telephones were hype, until every household had one. Email was hype, until ordinary people were sitting in front of a PC every day. GPS - arguably the most energy-intensive infrastructure project in the history of mankind - was hype (for consumers, at least) until everyone had a smartphone in their pocket. Technologies don't become essential because they're new. They become essential because they're boring. When is tech not hype? When it works so well we forget it's even there.

Let's talk about tabs

It honestly kills me to know that there are among the readers of this post almost certainly people too young to remember browsers before tabs. Inconceivable, right? And yet, would you believe me if I told you that, back in the late 90s, when tabs were first being added to browsers, their use was just as inconceivable as the alternative is now?

Why wouldn't you want to open a new window? It didn't make sense to the average browser user at the time. Browser tabs were considered eclectic, if anything - something for computer nerds to use. We were so used to stacking windows that none of us would have willingly made the migration to tabs. It had to be sold to us.

And yet, here we are, a quarter of a century later: you're reading this post in a browser tab right now.

The funny thing is, it wasn't even computer nerds who sold the tabbed interface to consumers. It was finance bros! It was the likes of Forbes and WSJ, writing for an audience who were familiar with tabbed interfaces from working with spreadsheets.

The tab as a concept arose in the 80s and found traction in the 90s after Borland released Quattro Pro, a spreadsheet app for power users. (You read that right: tabs started life as premium functionality.) Microsoft very quickly adopted the concept in its Office suite, responding to market demand.

You see where the hype loop starts to come in here, right? By 1993, Excel files have "workbooks", tabs that are saved, baked into the file format: you cannot open an Excel file without support for tabs.

NetCaptor v7.5.4 on SoftPedia

NetCaptor v7.5.4 on SoftPedia

Increasingly, the tabbed interface becomes a symbol of prestige. Preferring tabs to windows marks you as a member of the in-group who know how the world really works. In 1997, the first tabbed browser appeared on the scene: SimulBrowser, later known as NetCaptor, would find a niche market among power users, but its widespread adoption was hindered by its reliance on IE's Trident engine, with all its flaws.

Nevertheless, the box had been opened. A small but growing market of browser users wanted tabs in their browser. Opera was the first to deliver, but users had to pay for a license - or see ads in the browser. It wasn't until Firefox's free and open source alternative landed - accompanied by a very aggressive and high visibility marketing campaign (something Opera never bothered with) - that users made the switch en masse. Microsoft added tabs to IE two years later.

Cognitive Infrastructure

Here's the thing about browser tabs. It would be easy to argue that they use screen real estate more efficiently, or that the "The Way It Used To Be" metaphor was fundamentally more user friendly than windows. Both of these arguments would be missing the point. What makes tabs so powerful is what they do to our brains.

Have you ever wondered where all the 90s jokes about "browsing history" come from? Have you ever actually looked at your browsing history? Would you believe it was a lot more common back in the day? It was the only way we had to find something we'd switched away from. If we'd neglected to bookmark something, once we closed it it was gone. Tabs solve this. Tabs give us "parallel context", a kind of "working memory" - and by doing so, they create an entirely new problem.

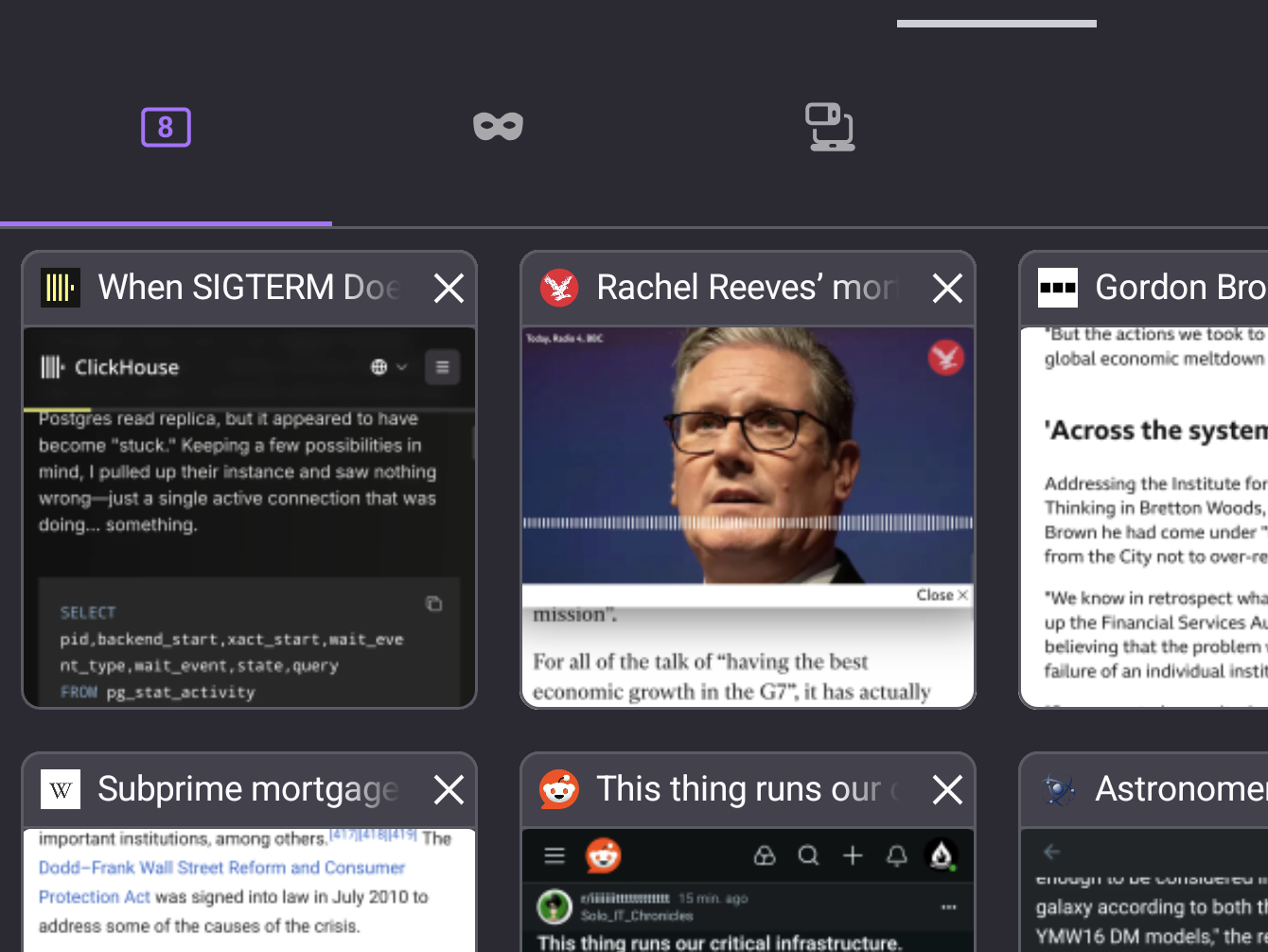

Have you ever gone for a walk along a busy street and wondered to yourself what it might be like without all the noise pollution and, indeed, the pollution pollution coming from cars? But there is nothing about a road, per se, that means it has to be polluted. Now look at your browser tabs. How many have you got open? If you're like anywhere from 30% to 55% of the population, the answer is: too many. Your tabs are polluted.

Browser tabs in a mobile browser

Browser tabs in a mobile browser

This is because tabs aren't just an interface. They are infrastructure.

From hype to habit

This is what real tech transformation looks like: it disappears. Try pitching a product to any VC today with the big selling point: it has tabs. Yawn! No-one cares. Tabs are basically the minimum expected at this point - if tabs make sense in your app and you don't have them? You better be doing something innovative.

Why? Because we think in tabs now. They are ubiquitous.

I said above all tech is hype. This isn't quite true: the definition of tech that's "not just hype" isn't what is innovative but what is insistent. Whether it disrupts or destroys is largely irrelevant - what's relevant is whether it survives. The difference is no more or less than the way it ends up being ignored: it either fades into obscurity because no-one uses it, or it fades into the background because everyone does.

All of the everyday tech we take for granted started out as hype. We say that tech is "not just hype" only ever in hindsight, after the interface and the infrastructure are already embedded. The hype cycle creates a bubble that bursts, causing more or less financial damage, whether the tech survives or not.

And some tech does indeed survive. It survives when it goes from being eclectic to being expected - when it works so well we notice it at all only when it breaks. There is no technology that does this when it's first invented. The hype cycle is there to will the supporting ecosystem into existence. When that process fails, that's when the tech dies out, and we say it "was just hype".

All tech is hype - until it's not.