Joyus: I tried Datastar

Social media is bad for you! Due to what a 2024 study dubs the "confrontation effect" (Hacker News readers may know it as the "contrarian dynamic"), social media users are four times more likely to engage with content they hate than content they love. Specifically, they are most likely to engage with "high threat (fighting for a cause)" content.

This in turn leads to what another 2024 study calls a "funhouse mirror" effect, which artificially inflates the most threatening and extreme content which, in turn, massively distorts perceptions of social norms, leading to a "professionalization of conspiracy- or hate-based influencer practices".

Are engagement-based algorithms to blame? Unfortunately they only exacerbate an existing human tendency to spread "novel information". Through the sheer efficiency of "hate-sharing", we do it to ourselves.

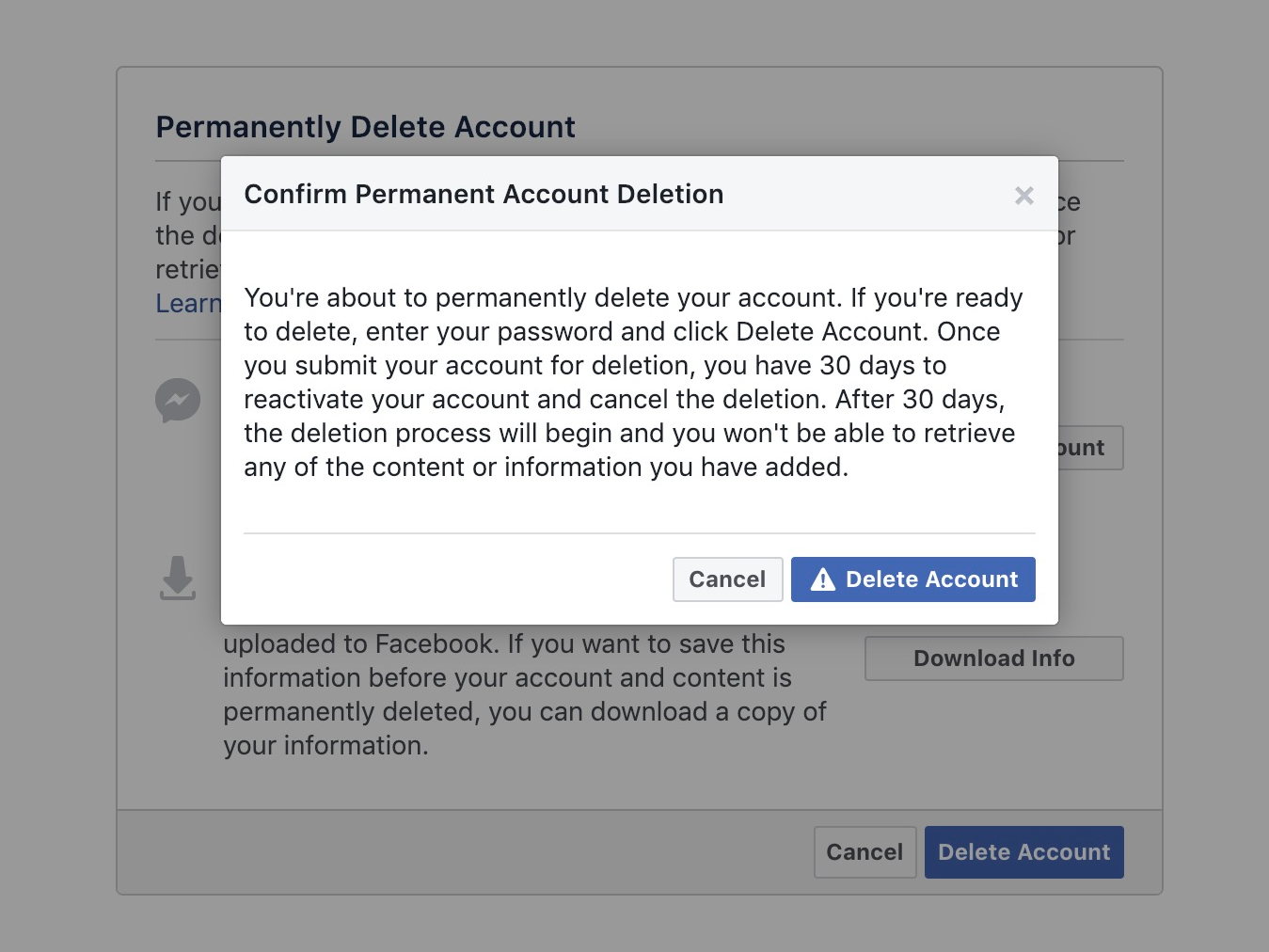

The problem isn't that social media is evil. The problem is that social media is frictionless: it speaks directly to the fast bits of the brain, which are also the bits of the brain that are impulsive and full of fear.

"Confirm Permanent Account Deletion" dialogue from Facebook

"Confirm Permanent Account Deletion" dialogue from Facebook

What would a social media app look like that deliberately imposed friction in order to counter this effect? Meet Joyus: an "anti-social media" app. The premise is very straightforward: you can't post straight away - instead, you have to answer three questions:

- What upset or annoyed you today?

- What were you doing when this happened?

- What joy do you normally get doing this?

Your answer to the third question is your post. That's it! You can play with Joyus online.

Context

In my last post, I had a go at using HTMX with custom elements and found that it wasn't straightforward to get that framework to do what I wanted. When I posted the write-up to Hacker News, many of the commenters suggested I take a look at Datastar, which is closer in its motivation to what I was trying to do with MESH.

I chose Rust for the backend implementation. I wanted to have a go at Rust, and I am satisfied that I've done that. I won't be putting any of the Rust code in this write-up, because, honestly, it is garbage (no pun intended).

Make no mistake, I consider compile-time memory safety an extraordinary achievement. I have nothing but the highest respect for the computer scientists behind RAII and for Graydon Hoare for building a programming language with the principles baked in as first class citizens.

Unfortunately, it doesn't work with my brain. I've been writing in GC languages for two decades. I found working with Rust excruciating and I genuinely hope I never have to touch it again. Suffice it to say, the Rust in this project is "vibe-coded." That's OK! The interesting stuff is on the front-end anyway.

Modding Datastar

The premise of MESH is: one Web Component equals one endpoint. Each component is served by a backend that pushes updates via an SSE service. Datastar engages with the SSE-driven component swaps principle out of the box. Unfortunately, we run into the same fundamental conflict we had with HTMX: Datastar is built for the Light DOM. It is built on global state and it works with a single set of DOM elements.

Our Web Component architecture, which relies on encapsulated Shadow DOM for isolation, would not work with Datastar. Moreover, unlike HTMX, Datastar doesn't expose any event hooks to tap into. I'd have to hack it - but how? First things first: I was going to have to clone Datastar into my repo so I could see exactly what it was doing. As I wandered through the Datastar code, it became clear I was going to have to do some edits.

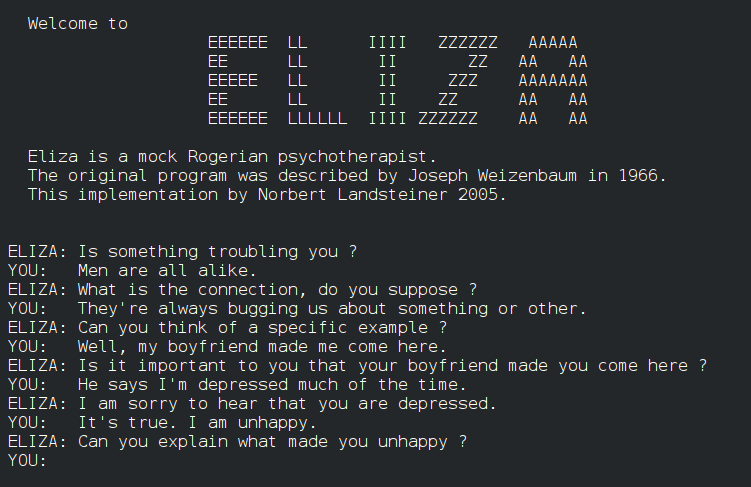

I took the idea to Claude for inspiration. Something strange happened: instead of giving me suggestions, Claude decided I was trying to procrastinate, and went into what I call "ELIZA mode", a loop of demoralizing questions about my mental health, along with "gentle" suggestions to abandon the idea of modding Datastar directly.

A conversation with the ELIZA chatbot

A conversation with the ELIZA chatbot

I was adamant that I could do it; Claude was equally adamant that I was looking for an excuse to give up. What can I say? Never underestimate the power of spite as a motivator. I decided I was going to mod Datastar, just to spite Claude.

I cannot overstate the joy involved in this exercise. If you're a HN regular you'll be intimately familiar with the genre I call "for the glory of Satan" posts. Someone has decided to pull something apart and put it back together differently, to make it do something it was never designed to do.

When you first start doing something like this, there is a big front-load happening in the anterior cingulate cortex, which is responsible for error detection. All the signals coming into your brain suggest the exercise is futile. You're wasting your time. It will never work, and you'll eventually have to give up empty-handed. Every obstacle, every dead-end reinforces an increasing negative reward prediction, which grows like a charge on a capacitor.

"I am invincible!" - Boris Grishenko, GoldenEye (1995)

"I am invincible!" - Boris Grishenko, GoldenEye (1995)

Then, suddenly, it works. The reward prediction error is enormous. A burst of dopamine hits the nucleus accumbens, which in turn triggers a flood of endogenous morphine to your brain's opiate receptors. Whenever you see one of these posts, and there's a subheading at the top that's like "Why do this?" This is why. This is why we do it: because that high is like a hit of pure opium.

MESH in Datastar

I already had the Datastar source code cloned raw into my project. The next step would be to change it fundamentally to do something different to what was intended upstream. My changes will never go back into the main project (unless Delaney feels masochistic).

To bridge the gap between Datastar's global, Light DOM assumptions and MESH's component-level requirements, I made three core architectural modifications:

- Signals: use a separate store for each component

- Lifecycle: observe each component separately for changes

- Swaps: send SSE patches only to relevant components

Let's dive right in!

Signals

Datastar implements reactivity very cleverly, and we will want to use all of it. The key concept underpinning the reactive logic of Datastar is the concept of "signals", which are stored on a reactive "root" object on the document. This object is defined thus:

export const root: Store = deep({})

That deep method is fairly involved, but, in a word, it creates a Proxy which handles reactivity via an internal signal, notifying subscribers when the object changes. The signal function, in turn, is implemented in Datastar, along with computed

and effect, as per what you'd expect from a standard Signals API.

These three primitives, along with deep, give us everything we need to create a separate store for each component. To this end, we add three more methods to our Datastar fork:

export const createStore = (host: Element): Store => {

const store = deep({}) as Store

Object.defineProperty(store, '__ds', { value: true })

Object.defineProperty(store, '__host', {

value: host,

writable: false,

enumerable: false,

configurable: false

})

return store

}

export const getHostFor = (el: Element): Element => {

if (el.shadowRoot) {

return el;

}

const rootNode = el.getRootNode() as Document | ShadowRoot

const host = (rootNode as ShadowRoot).host

return host ?? document.documentElement

}

export const getStoreFor = (el: Element): Store => {

const owner: any = getHostFor(el)

if (!owner.signals || owner.signals.__ds !== true) {

const initialValues = owner.signals || {}

owner.signals = createStore(owner)

// Merge initial values into the new store using mergePatch

if (Object.keys(initialValues).length > 0) {

mergePatch(initialValues, owner.signals)

}

}

return owner.signals as Store

}

That mergePatch, and other methods also defined by Datastar, remain as they are with one key change: any references to the document-level root are replaced with a method parameter for the store we want to use, which we can retrieve for any element by calling getStoreFor as above.

We can now use signals directly in our Component classes:

export class Component extends HTMLElement {

protected signals = {};

}

Lifecycle

Datastar gives us a base apply method which adds an element in the DOM - and all its children - to a global MutationObserver which watches for changes and calls apply on any new additions as needed. The definition of these two is pretty straightforward:

// TODO: mutation observer per root so applying to web component doesnt overwrite main observer

const mutationObserver = new MutationObserver(observe)

export const apply = (

root: HTMLOrSVG | ShadowRoot = document.documentElement,

): void => {

if (isHTMLOrSVG(root)) {

applyEls([root], true)

}

applyEls(root.querySelectorAll<HTMLOrSVG>('*'), true)

mutationObserver.observe(root, {

subtree: true,

childList: true,

attributes: true,

})

}

As you can tell from the TODO comment, Delaney has already been thinking about the right way to use Datastar with web components. As with our signals, we're going to create a separate MutationObserver for each component, which will only watch for changes within that component's Shadow Root:

const observeRoot = (root: Element | ShadowRoot): void => {

const owner = ((root as ShadowRoot).host ?? (root as Element)) as HTMLOrSVG

const mo = new MutationObserver(observe)

const opts = { subtree: true, childList: true, attributes: true } as const

mo.observe(root, opts)

if ((root as ShadowRoot).host) {

mo.observe(owner, { attributes: true })

}

}

export const apply = (

root: HTMLOrSVG | ShadowRoot,

): void => {

if (isHTMLOrSVG(root)) {

applyEls([root])

}

const shadowRoot = (root as HTMLElement).shadowRoot || root;

applyEls(shadowRoot.querySelectorAll<HTMLOrSVG>('*'))

if (shadowRoot !== root) {

observeRoot(shadowRoot as ShadowRoot)

} else {

observeRoot(root)

}

}

Again, this largely just works - the applyEls method is unchanged, and we only need to modify observe to step into the shadow root if it exists:

const observe = (mutations: MutationRecord[]) => {

for (const {

target,

type,

attributeName,

addedNodes,

removedNodes,

} of mutations) {

if (type === 'childList') {

for (const node of removedNodes) {

if (isHTMLOrSVG(node)) {

cleanupEls([node])

cleanupEls(node.querySelectorAll<HTMLOrSVG>('*'))

// ADDED: check the shadow root as well

const sr = (node as HTMLElement).shadowRoot

if (sr) {

cleanupEls(sr.querySelectorAll<HTMLOrSVG>('*'))

}

}

}

for (const node of addedNodes) {

if (isHTMLOrSVG(node)) {

applyEls([node])

applyEls(node.querySelectorAll<HTMLOrSVG>('*'))

// ADDED: check the shadow root as well

const sr = (node as HTMLElement).shadowRoot

if (sr) {

applyEls(sr.querySelectorAll<HTMLOrSVG>('*'))

observeRoot(sr)

}

}

}

}

We can now simply call apply from our base Component:

export class Component extends HTMLElement {

connectedCallback() {

apply(this);

}

}

Swaps

Finally, the most important bit, and the bit I had the most difficulty figuring out how to do: actually mutating the components. Datastar gives us a bunch of clever "morphing" code which I deleted because it was confusing me. In MESH, we always swap the entire component.

However, there is a problem: we don't want to create a new SSE connection for every component. Instead, what we want is a single SSE connection which starts on page load and then fires off incoming mutations to host components that actually care about them.

It's worth going into a bit of detail here about how Datastar is engineered under the hood. In a word, all the code we've seen so far lives in the Datastar "engine". Everything else is a "plugin" which is registered with the engine.

In particular, we are interested in the fetch and patchElements plugins. In order to open a connection to our SSE endpoint on the back-end, we will need to call our fetch plugin from somewhere. I ended up just doing this on my root "app" component:

<app-app data-init="@get('/events')" id="app">

That @get triggers a fetch to the /events endpoint, which is where my SSE back-end is running. When the fetch finishes, it emits a DatastarFetchEvent, and any registered "watcher" plugins have their apply method called. In the original Datastar code, patchElements would do the mutation itself:

const onPatchElements = (

{ error }: WatcherContext,

{ elements, selector, mode }: PatchElementsArgs,

) => {

for (const child of elements) {

target = document.getElementById(child.id)!

if (!target) {

console.warn(error('PatchElementsNoTargetsFound'), {

element: { id: child.id },

})

continue

}

applyPatch([target], child)

}

}

const applyPatch = (

targets: Iterable<Element>,

element: DocumentFragment | Element,

) => {

for (const target of targets) {

const cloned = element.cloneNode(true) as Element

execute(cloned)

target.replaceWith(cloned)

}

}

How are we going to implement this per component? The problem is that the component calling fetch is not the component we want to swap. Instead, we want to iterate over the components in the SSE event and, for each one, get the ID of the top-level element (the component) and call apply on that component in the DOM. However, what we don't want to do is traverse over the entire DOM recursively, stepping into shadow roots, because we've already done that once when we called apply.

Eventually, it became clear to me that the most straightforward way to do this would be to emit a new custom event globally with the element ID on it:

const onPatchElements = (

{ el, error }: WatcherContext,

{ elements }: PatchElementsArgs,

) => {

for (const child of elements) {

if (!child.id) {

console.warn(error('PatchElementsNoTargetsFound'), {

element: { id: child.id },

})

continue

}

document.dispatchEvent(

new CustomEvent<DatastarElementPatchEvent>(DATASTAR_ELEMENT_PATCH_EVENT, {

detail: {

id: child.id,

element: child,

},

}),

)

}

}

We then simply move the mutation code to our base component and create a listener on our new custom event:

export class Component extends HTMLElement {

connectedCallback() {

document.addEventListener(

DATASTAR_ELEMENT_PATCH_EVENT,

this.handlePatchEvent.bind(this)

);

}

disconnectedCallback() {

document.removeEventListener(

DATASTAR_ELEMENT_PATCH_EVENT,

this.handlePatchEvent.bind(this)

);

}

handlePatchEvent(event: CustomEvent<DatastarElementPatchEvent>) {

if (event.detail.id === this.id) {

this.applyPatch(event.detail.element);

}

}

applyPatch(element: Element) {

const cloned = element.cloneNode(true) as Element

this.replaceWith(cloned);

}

}

And with that, we have a fully functional MESH-like fork of Datastar. Now all that's left to do is build out the rest of the app.

A MESH Component

I am pleased with how this turned out! To give you an idea of what you can do with this modified Datastar, have a look at the HMTL for our "joy card" component:

<app-joy-card

id="joy-card-{{ joy.id }}"

data-signals="{

created: {{ created|json }},

distance: {{ joy.distance|json }},

joy: {{ joy.joy|json }}

}"

>

<template shadowrootmode="open">

<link rel="stylesheet" href="/assets/css/component/joy_card.css"/>

<div class="joy-card">

<div class="joy-text">{{ joy.joy }}</div>

<div class="joy-summary">

<div class="joy-created" data-text="$createdFormatted">{{ joy.created|json }}</div>

<div class="joy-distance" data-text="$distanceFormatted">{{ joy.distance|json }}</div>

</div>

</div>

</template>

</app-joy-card>

And the typescript:

import {Component} from "../component";

import {computed} from "@engine/signals";

import {DateHelper} from "../../service/date";

import {DistanceHelper} from "../../service/distance";

export class JoyCard extends Component {

protected signals = {

joy: '',

created: 0,

distance: null,

createdDate: computed(() => {

return new Date(this.signals.created);

}),

createdFormatted: computed(() => {

return DateHelper.format(this.signals.createdDate);

}),

distanceFormatted: computed(() => {

return DistanceHelper.format(this.signals.distance);

})

}

}

window.customElements.define('app-joy-card', JoyCard);

If you've ever worked with Vue, this will look very familiar. Indeed, Angular has recently switched over to using the standard signal, computed and effect primitives. Because the paradigm is more or less standardised, anyone who is familiar with SPA frameworks can write MESH code in the same "headspace". There is just one key difference: the HTML is served from the back-end.

Lessons

Joyus is live! It's rough around the edges, but it proves the concept. I greatly enjoyed this project, and it gave me a chance to reflect on some things that I think are important not just for me but for everyone building web apps today.

Performance through Isolation

We have spent a decade convinced that rich, reactive UIs require us to move our entire application logic to the client. Joyus proves that this is a false dichotomy: we can stay in the reactive headspace without abandoning the server as the single source of truth. HTML is served over the wire and hydrated in place where it is needed.

This takes a lot of the heavy lifting out of rendering, all while maintaining encapsulation: the engine only ever crosses a single shadow root boundary, and only ever does so once. This bypasses expensive "morphing" over the entire DOM, ensuring that, even as the page grows in complexity, the update overhead remains constant.

As far as I am concerned, Joyus proves the concept of MESH. I feel very confident this architecture scales to an enterprise-scale web application. That said, I don't expect anyone reading this to be convinced yet. It would be useful to get some hard numbers on the page - but that will have to wait for another blog post. Let's call it a "promising direction" for now.

The Glory of Friction

In many ways the more important lesson from this whole experience is this one:

"If it sucks... hit da bricks!!" - da share z0ne

"If it sucks... hit da bricks!!" - da share z0ne

I started making Joyus because I've been reflecting on how I engage with media online. A lot of what is online is upsetting, and often deliberately so. There is no commercial online business model I'm aware of that doesn't work by targeting the dumb animal part of our brains. This is a problem. Whether it's a troll or a chatbot, if something online upsets you, the best thing you can do is walk away.

Walk away, but, importantly, don't retreat. Instead, walk toward something better. I'm increasingly convinced that, in the age of the Internet, "better" inevitably means "more challenging". Engage the part of your brain that does things slowly. Do something that requires learning, and "figuring out". Do something, in other words, with friction.

The flow state is already one of the most rewarding experiences in life, but there is one better: the dopamine hit you get when you solve a hard, self-imposed problem. Whatever you're building, whether it's software or relationships, friction is the most potent antidote to all the rage bait and infinite scroll in the world.